On Haibane Renmei: life, loss and redemption

By almost any measure, Haibane Renmei is odd. Perhaps because its creator came from a different type of artistic training from most people in the anime and manga industries, it certainly looks different. Character designs aside though, it’s still a very unusual piece of television that’s hard to compare with anything else: it’s one of those examples of a production being its own thing. On one hand, this makes it hard to recommend because there’s not much else out there (at least as far as I know) to provide a frame of reference. On the other, it’s one that I’d mention to someone who is tired of common tropes and wants to experience something that’s simultaneously escapist yet easy to relate to.

When it was first released on home video, I recall other viewers pointing out similarities between its setting and one of those depicted in the Haruki Murakami novel Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. While I remember these details being widely accepted – and having read the novel, I noticed them at the time too – I’ve not yet been able to find an interview with the cast or crew to confirm this little factoid. Even Wikipedia states “citation needed.”

It's been many years since I read the book, but I doubt that the two works are set in the same world/universe, and I don’t think that you need to read/watch one to appreciate the other. My suspicion is that Yoshitoshi ABe wanted to set his story in a closed-off sort of place and used “The End of the World” as a tribute to a novel that he enjoyed. Incidentally, a minor subplot of Haibane Renmei is a book titled “The Start of the World” which is…a little on-the-nose if the parallels are indeed deliberate!

Like many other parts of the show’s background, it’s a bit of a distraction to dwell on this too much, because it’s really just part of the aesthetics rather than an important message that the show is trying to convey. This is an issue I often have with stories that rely heavily on metaphor to get their points across: it’s sometimes hard to discern what’s included because it’s meaningful and what’s included simply because it looks cool or impressive, so some people are tempted to dismiss it as pretentious.

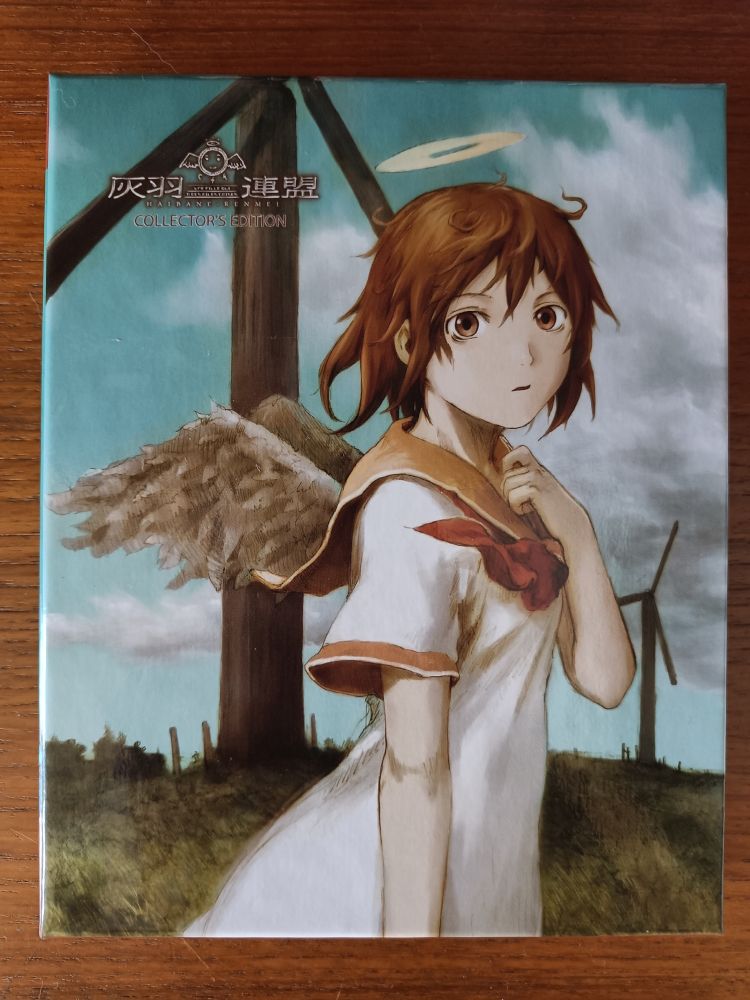

Another concept that viewers are at risk of mis- or over-interpreting is the supposed religious symbolism. My impression is that a Haibane’s wings are a visual indicator of their “otherness” alongside ordinary humans, and the “rings” above their heads are another very deliberate attempt to show them as different but not divine. After all, traditional depictions of halos in religious art are often a disc or radial diffuse beam of light, not a piece of solid metal hovering horizontally over its owner’s head. In that sense, the Haibane are visibly neither supernatural nor entirely human and they are treated as such by the townspeople, even though the specifics are lost in the fog of the town’s collective memory.

There are a couple of comedic moments related to the rings/halos, but the scene where Rakka’s wings appear is a great example of how visceral and striking fantasy-drama can be without doing anything loud or flashy. Because the setting is almost completely cut off from the outside world, the events are small in scale and personal but I think that this helps keep the storytelling grounded and focused.

Despite its low-key approach, there’s a lot to admire here, even when it’s just there to make the visuals more interesting or when its ambition is restrained by the made-for-TV animation budget. The environment is wonderfully immersive, and is also dreamlike in a familiar-yet-strange sort of way. Because it’s an enclosed reality, the writers had free rein to be as down-to-earth or fantastical as they wanted without having to fill plot holes or justify its strangest elements. The last time I experienced such satisfying world-building was in Mari Okada’s Maquia feature film, which worked for me in a similar way that Haibane Renmei did. A lot of imagination had gone into the environments that the characters found themselves in, but there was enough lurking in the background or on the edge of the frame in many scenes to make me feel that we were being given a glimpse into a much larger worldview that was even more rich and complex. Not only did a lot of work go into the work itself, but it gave plenty of springboards for my imagination to jump from after the end credits rolled.

All of this can however lead the viewer on wild goose chases and circular trains of thought, not dissimilar to the “Circle of Sin” paradox that forms on of the show’s core themes. For all the evocative imagery and hints of complex culture and mythology that permeates everything within the ever-present walls, its messages are fairly everyday and straightforward, and I do worry that these trappings don’t always work to the show’s advantage.

It’s not always easy to draw yourself away from questions like, “where do the Haibane actually come from?”, “where do they go after their Day of Flight?”, “who are the Toga and the Communicator?” and numerous others besides, and this is probably the show’s main potential flaw. ABe made an effort to avoid tying the imagery and themes to any one religious or spiritual ideology, but I suspect that individual viewers’ opinions might differ on whether he succeeded (the Christian imagery is likely to resonate slightly differently and be more distracting among those of us from a Christian background who live in Europe, for instance).

Because, when you look past all that, the emotional core is very profound and relatable. There were lines of dialogue, such as Reki’s desperate plea of “what if I call from the bottom of my heart and no one answers?” that were a real punch to the gut. There are also broader discussions going on about friendship, finding one’s place in the world, and how to deal with grief and loss. Of course, this is all happening in a very strange place that’s clearly not part of “our” reality, but in spite of this it still stuck in my memory for over a decade after I first watched it and still resonated with me when I revisited it years later.

The soundtrack is another aspect that really deserves a special mention, being as it is an early example of anime music that that worked in its original context but also stood alone on its own merits. The Hanenone CD album was one of the first anime OSTs I ever bought, and is still a favourite of mine today. While Kow Ohtani quite rightly received acclaim for his work on the Shadow of the Colossus game and others, this is another one of his career highlights: much like the show itself, it’s in turns whimsical, introspective and emotionally moving yet is tantalisingly impossible to pin down to any particular time or place.

Ultimately, the main take-home message I got from this story was that there’s a lot of power in forgiveness, and sometimes the biggest hurdle is forgiving ourselves. Of course, this won’t apply to absolutely every situation or context, but I was left with an overwhelming sense of hope that the mistakes we make and the times when we hurt ourselves or others don’t necessarily define us or render us irredeemable: we can become better people as long as we put the work in. It reminds me of Lois Tonkin’s Model of Grief, which states that emotional wounds don’t always go away; we grow around them instead. Haibane Renmei seems to suggest a similar process, in which its characters find comfort and closure from past traumas, acknowledging them but still moving forward. Contrary to what we sometimes think, we’re not completely beyond help or hope.